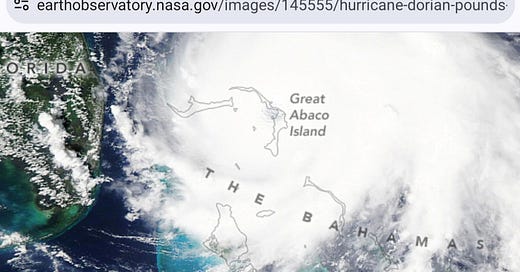

There is no greater natural force on earth than a Category 5 Hurricane. Dorian made landfall on the afternoon of September 1, 2019, at Elbow Cay, Abaco, Bahamas, and proceeded directly across the small but bustling city of Marsh Harbour; the utter destruction is still evident. In a never-before seen track, the storm struck with 185mph winds, rain and a twenty-two foot storm surge, moved on, and then returned, adding the fury of tornadoes, and lasted an agonizing, nearly apocalyptic 48 hours total. The country was caught wholly unprepared. While the official death toll is 68 and the official number of people missing is 245, the word from locals is that there were thousands of undocumented immigrants living in the northern outskirts of the city. That count is controversial. Everything and nearly everyone in those areas was simply gone. Six months after the disaster, in March of 2020, the fifty still-unidentified bodies that had been stored under refrigeration for far too long were finally put to rest. We met a survivor whose wife and child had been lost.

“I laid in the mud beside dead people. Everyone but me was dead,” Luke Cage said to me, looking sideways rather than straight on as he usually did. He turned, met my eyes and the story poured out. “I spent two days in the salt water, three days in the mud, and they went to put me on the dead list, and then I sneezed, and then they washed my face and lifted me up and then they carried me, I was bled out, completely. During the storm, I hit a piece of roof or something metal and it tore my scalp open,” he paused to show us the rough scar atop his skull. “They took me to Nassau, with a less than 50% chance to live… It’s not my time. I told them. If I was going to die I’d already be dead.”

He gathered his thoughts, and then continued, “That first doctor didn’t want to touch me, I was in bad shape and I smelled and he didn’t think I was going to make it.” Luke had been conscious while this was happening and he told them again, “God’s still living, and trust me God hasn’t taken me yet, so I’m not going. That’s what I told them, many times. It was the Haitian Doctor and nurse that saved me. I would not think, at that time, that it would make a difference where I was from; I had to keep telling them, I am Bahamian, I was born here. That first doctor came back to apologize and I told him, you don’t have to be sorry to me, you have to be sorry to God.”

He hesitated and I asked him if the community had known the storm was coming. He replied with a disbelief still vivid after all these years, “The only warning was that Marsh Harbour was going to be flooded. We had no idea, I don’t remember the wind as much…everything was underwater …all kinds of things mixed up together, so dirty. Can you imagine what was in there, the septic and the electric poles and wires and just everything…so dirty. Some people would have left you there in those times; but in this world there are always some people who would help you and some people that would not.”

Luke’s accent is very strong and, being born to Haitian parents, Creole, not English, is his first language. I haven’t written in the style of his dialect, but his fast, lilting inflection was often hard for me to transcribe, even more so when his voice caught with the emotion of telling his tale. Sadness emanated from his entire being; no language barrier there. After another silence, he went on, staring farther into somewhere we could not follow. “My wife and child went to check on her mother and the storm took them all. Just took them.”

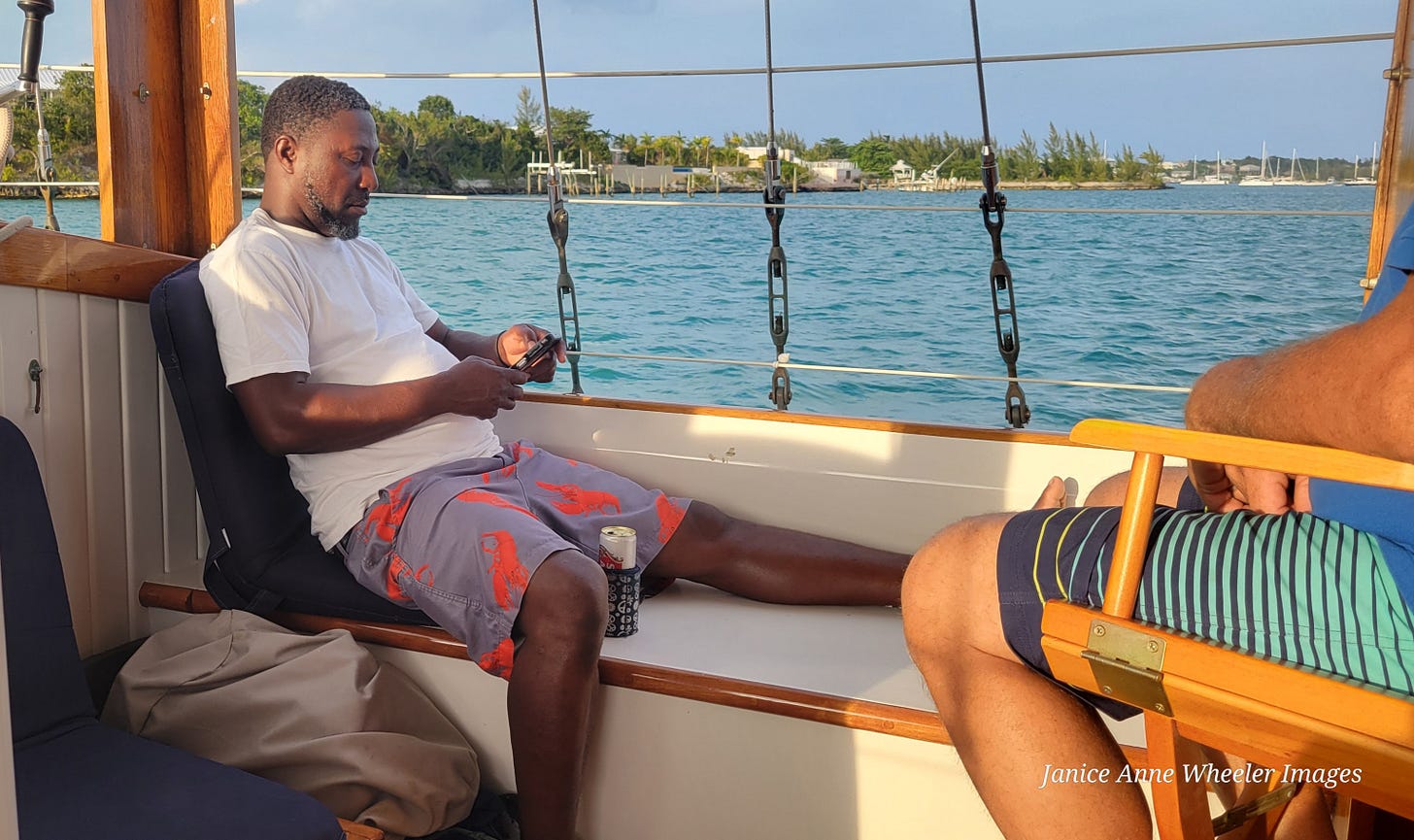

Steadfast had been anchored in Marsh Harbour on and off since March 21st, 2024. This genuine, handsome, hard-working Bahamian had come into our lives a couple of nights ago, when Steve decided he needed to make sure some of the good people he knew here as a child still lived, loved and thrived in the Abacos. He found Luke. He found what he was looking for.

I called him Saint Luke even before I had any grasp of just how much he believed in God, because he had looked out for the only American hanging out at the Creole Café that particular night. Then Luke showed Steve his home, Dundas Town, and an outskirt called, ironically enough, The Mudd, where other strong, honest, caring Bahamians hung out until the wee hours. They played dominoes, they took Steve in.

Born in 1985, Luke has knowledge and wisdom far beyond his eight years of formal education. “I was not going to let anything happen to Stevie,” he told me, laughing, and turned to Steve, “I had to make sure you were safe. I watched you the whole time, when I dropped you; your little boat got out to your big boat and then you stepped onto the big boat and then I called you just to make sure.” He tells this with a big easy smile. “We will be friends forever. God sent you to me, I don’t know why.”

The first time I met him, Luke hugged us both, hard, and then drove us back to The Mudd, Steve in the back of the pick-up, to a little six-seat waterfront bar and restaurant that had recently reopened. Businesses, homes and docks on either side had been demolished and not rebuilt, two boats were sunk just offshore. Haitian immigrants, mostly undocumented, occupied this area for decades prior to Dorian. It was those families, Luke’s and many others, that were swept unmercifully into the North Atlantic when Dorian traced his path. Some estimates support Luke’s thinking that there are as many as three thousand lost souls. We will never know.

“I was in that hospital for maybe a month. I came back to nothing. Everything was gone. I didn’t save anything at all. Even my documents. Nothing. I just wanted to see my wife and child one more time. So bad. I kept asking for them. I think I went to Nassau and back, giving DNA samples and everything, maybe thirteen times, but they really were not able to help, it was too many, and they didn’t have anything. They didn’t have resources. I’m not going to lie, I was crazy. I was crazy.” That was worth repeating because he did, a third time, too. “And then they had the mass burial and I said, I just need to see my wife and child, I was so desperate, and the officer pulled a gun on me. Everyone went a little crazy then, it made the news and all of that because it just made no sense, I think. Of course they never found her, never knew where she died. And I did think, ‘What do I have to live for?’ But we all went forward and did the cleanup and did what we could do… I have been through so much,” he shook his dark, gray-tinged, perfectly groomed head, and turned it away, as he had the first time we broached the subject.

“I can’t fathom it,” I told him, unintentionally throwing him off with that terminology, and stopped typing to gaze across that water and realize that all of this had happened only a few hundred yards from here. I rephrased, “I don’t know what to say.” I told him, because I didn’t. “I’m sorry,” seemed remarkably inadequate but Steve and I repeated it numerous times over the course of the retelling. I had asked Luke beforehand if I could write his story, and he agreed, appearing comfortable even when I pulled my Mac out and started capturing his words.

“The storm changed everything,” he confided quietly, “and everyone.” We fell into silence. He took a swig of his Michelob Ultra and declared, with the certainty of the faithful, “…Now I know that you don’t need a funeral and a casket and all of that to get to heaven, to get to God. God is good. God took one child but he left me the others.” No matter what you believe or what you don’t believe, sometimes there is nothing you can do to save who you love.

The region has come a long, long way, but less than half of the homes have been rebuilt or businesses reopened and reminders are everywhere. Many residents moved to Nassau or Freeport when they lost everything. The entire aquifer of Grand Bahama was flooded with dirty salt water, rendering no fresh water for years. The scale and challenges of such a tragedy are monumental.

I am honored that Luke told me his story. Next week I will share another personal account of facing down and surviving Hurricane Dorian.